The Bishop's Justice

In the Lafayette Diocese, priests who abuse are judged on a distinction

critics find outrageous: Were the victims teens, or children?

By Linda Graham Caleca and Richard D. Walton

Indianapolis Star

February 17, 1997

[See links to all

the articles in this series from the Indianapolis Star.]

Priests accused of sexual abuse or misconduct in the Lafayette Diocese

face neither a judge nor jury.

They answer to a bishop.

And William L. Higi's system of justice is ill-defined, infuriating to

victims – and, some fear, dangerously misguided.

Higi's law is based on a maze of church canons, state statutes and psychological

theories still under wide debate.

|

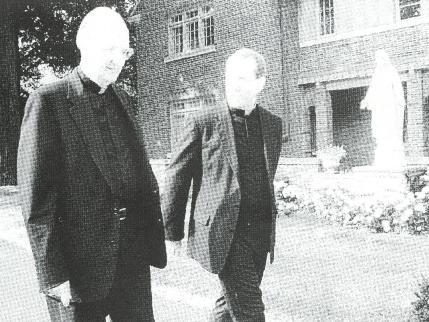

| In Their Court: The fates of sexually abusive priests are in the hands of Bishop William Higi (left) and his vicar general, the Rev. Robert Sell. Basing their decisions largely on victims' ages, the men call their approach responsible. Detractors call it wrongheaded and risky. Staff Photo / D. Todd Moore. |

Instead of prison, perpetrators go to therapy. What happens next may

depend less on the trauma they inflicted than on their victims' ages.

Molest a young child, Higi says, and you're finished as a priest.

But abuse a teen and there are options. With counseling, you may return

to the ministry. In practice, though, abusers have slipped out of town

and begun new lives outside the priesthood.

Child molesters cannot be cured, Higi explains, but men who prey on teens

can.

His second-in-command takes that belief a surprising step further.

Some teens, Vicar General Rev. Robert Sell suggests, might be partly responsible

for their own abuse. Unlike "innocent" children, he says, teens

can "consent" to sexual acts.

As young as 13, says Sell, who investigates the diocese's abuse cases,

there can be "an element of consent, as well as an element of understanding

of what is morally right and wrong."

The bishop doesn't go that far. He dismisses as irrelevant the idea of

consenting teens. Yet Higi calls it "consenting" when priests

have sex with young adults – even parishioners. He lets those priests

return to the pulpit after therapy.

Critics call this system of discipline offensive and wrongheaded.

It misses the larger point – that priests have promised to refrain

from sexual relationships altogether, says the Rev. Melvin Bennett of

St. Bernard Church in Crawfordsville.

|

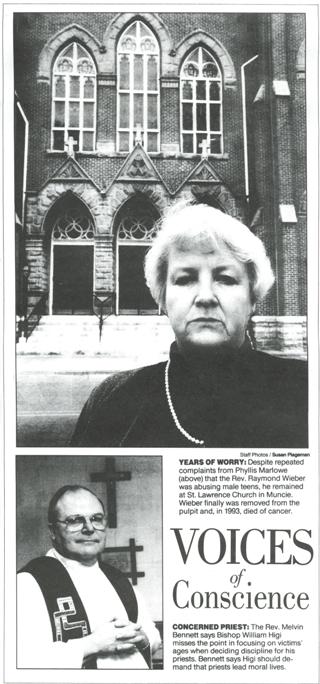

Instead of worrying about victims' ages, Bennett says, church officials

should be talking to priests about "living a celibate life and living

a chaste life.

"And being men of prayer."

If the diocese's approach is misguided, it is also convenient.

While no one suggests that Higi and Sell devised the system for expediency,

it does allow them to cast a terrible problem in the best light.

In a Roman Catholic diocese long plagued by accusations of sexual abuse

and misconduct, only a fraction of the accused preyed on young children;

more abused teens. So Higi and Sell can downplay the bulk of the offenses

and truthfully tell the public their pedophiles are few.

The diocese can justify its more lenient treatment of abusers of teens

because those offenders are not, as Sell puts it, "the extreme predator"

a pedophile is.

Consider the cases of Monsignor Arthur Sego and the Rev. Ron Voss –

both longtime friends of the bishop.

Sego, who sexually abused girls, lives a restricted life in a rest home

on Higi's orders. He cannot come and go without supervision.

In contrast, Voss, who was accused of abusing eight male teenagers, is

a free man in Haiti. He resigned the priesthood in 1993.

"The man just doesn't understand (sexual) boundaries," Higi

says of abusers such as Voss.

"There are many people in this country who engage in this ... older

people that get involved with younger people."

Infuriating Distinction

Angry victims say comments like that minimize the pain caused by Voss

and other predators of vulnerable teens. They say these abuses were no

less horrific – and the perpetrators no less guilty.

A grief-stricken mother, who says her son was victimized by Voss at age

13 or 14, can hardly believe that Higi draws a line between children and

adolescents.

She says her son died a traumatized young man after Voss sexually abused

him years earlier.

That central Indiana woman asked that her name not be used, but wanted

the bishop to remember that Voss did a terrible wrong.

He hurt children, she reminds Higi. "It's child molest."

Under Indiana law, the age of consent is 16. Sexual acts with children

under 14 are felonies, whether the victim is willing or not.

Yet priests who ignored those laws went not to court, but to Higi. Diocese

officials insist they followed the law by reporting child abuse to authorities.

That could not be confirmed because those reports are confidential. But

no criminal prosecutions are known to have resulted.

In place of the legal system, the church becomes the law. Higi insists

that he acts promptly and responsibly.

He stresses that any priest guilty of sexual abuse or misconduct has committed

a wrong. But he sees degrees of wrong and believes that any man who is

not a dangerous pedophile stands a chance of rehabilitation.

This is how Higi and Sell explain it:

• Pedophiles, who prey on children under age 13, can never again

function as priests. They suffer a severe and lasting psychological disorder.

• Ephebophiles, who are attracted to teen-agers, can learn to control

those sexual urges with therapy. They may be allowed to return to some

form of God's work.

No abusers of teens currently are in the Lafayette Diocese. Only after

rehabilitation, Sell says, could any return in the future.

Abusers, though, don't always fall into a clear category.

The Rev. Ken Bohlinger says he hardly knew – or cared – whether

the boys he sexually abused were 9, 10, 12 or 14.

Asks Bohlinger, a former Anderson priest: "Are you an alcoholic just

for beer? Are you an alcoholic just for wine? Are you an alcoholic just

for the hard stuff?"

"I'm attracted to children, period."

Psychological debate

Higi did not pull his system of discipline out of thin air. He says it

is rooted in psychological research and expert opinions.

One noted expert is the Rev. Canice Connors, the immediate past president

of St. Luke Institute in Silver Spring, Md.

Connors concedes that experts who talk about teen abusers can sound like

they are trying to "excuse" the behavior. Far from it, he says,

ephebophiles must be held accountable.

Still, Connors believes a pedophile is a "much sicker person."

Cures are rare, he says, for molesters who are obsessed with a child's

smooth skin, hairless body and small genitals.

Those who abuse teens suffer more from low self-esteem, Connors says.

They just can't believe that any adult would be interested in them. With

therapy, many can learn to control their urges and, under supervision,

return to some type of ministry.

Easier said than done, counters Fort Wayne psychologist John Newbauer.

Normally, he said, men attracted to teens can be treated by helping them

focus instead on healthy relationships with adults.

But for priests pledged to celibacy, Newbauer said, there is "nowhere

to go with their sexual fantasies."

Curing either abusers of children or teens is difficult, stresses Dr.

Fred Berlin of Baltimore who sees little distinction between pedophiles

and ephebophiles.

"I wouldn't use the word cure with any of these people," said

Berlin of the National Institute for the Study, Prevention and Treatment

of Sexual Trauma. "Both are serious circumstances."

Berlin urged church officials to remember that teens are very much like

young children. Maturity levels do not always match ages, he says.

So it is wrong "to be debating the age of consent among children."

As an advisor to the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, Berlin sees

bishops struggling to understand these issues. He advises them to deal

honestly with the community and to "err on the side of public safety."

With Voss, critics charge, Higi did not.

Voss held onto his priesthood for five years after he first was accused

in 1988 of sexually abusing a teen-ager. He went to therapy and moved

to Haiti.

Higi calls the former priest a "success story for rehabilitation."

Noting that Voss regularly sees a therapist, the bishop says there is

no reason to worry about Voss' sexual behavior today.

Berlin worries anyway.

Voss comes in contact with young Haitians; he works with parishes and

has also taught English.

A man with Voss' history should "not be somewhere else where vulnerable

youngsters can be victimized by him," Berlin said.

"Kids are just as important in Haiti as they are in a hometown of

Indiana."

Salvation of souls

Muncie was the Rev. Raymond Wieber's town.

Even though Wieber, of St. Lawrence Church, was accused of repeatedly

abusing a teen-age altar boy, Vicar General Sell says the diocese considered

bringing the priest back after his therapy.

"It was our hope that he would come back to some type of ministry,"

says Sell.

Sell, who was a friend of Wieber's, notes that the "salvation of

souls" is a supreme law of the church and an important goal in these

cases.

He says Wieber might have been allowed to minister at a nursing or retirement

home, a place teens didn't frequent.

In 1993, before Wieber's fate could be decided, the priest died of cancer.

That officials even considered returning him to ministry outrages Phyllis

Marlowe. A devout Catholic from Muncie, she says it's "just enough

to make me quit the church."

For years, Marlowe suspected Wieber's abuses. She lived behind St. Lawrence

and heard accounts of sexual acts from teens who visited Wieber's church

or rectory. When she complained to Bishop Raymond Gallagher, he told her

Wieber had been to therapy and no longer posed a problem.

Years later when Higi was bishop, Marlowe complained again, this time

about Wieber abusing the altar boy. She learned of the abuse long after

Wieber preyed on the youth, who was one of 10 children in a family whose

father had died. Marlowe, the mother's friend, said Wieber exploited the

tragedy.

Higi immediately sent Wieber to therapy, but death ended his ministry.

"He was finally removed." said Marlowe, the Delaware County

recorder. "God did it."

Although it is possible for priests who abuse teens to return to ministry

under Higi's system, the fate of child molesters is more certain. Their

careers in the priesthood are finished, the diocese says.

Though Sego, like the others, escaped prosecution and prison, he did receive

some punishment from Higi.

At the rest home. Higi says, Sego is essentially under "house arrest."

The bishop's voice flared with anger as he spoke of Sego, his former second-in-command.

"I think house arrest is a good term because it is very difficult

for him to be where he is," Higi said. "He is not free to come

and go at will."

In an interview, Sego said he had no idea why the bishop treated him more

harshly than all the other accused priests. But he disputes that his home

is a jail.

"I am in a very quiet, beautiful rest home out in the woods,"

Sego said. "We are just out in the country, and you can't see anywhere

but up."

Sego is lonely, though, and wants to come home to his family in Indiana.

But he depends on the church financially, and he must do as his bishop

asks. At least for the time being, Sego says, Higi won't let him return.

Pedophiles, Higi says, will never be tolerated in his diocese. "Even

one case of pedophilia," he said, holding a finger in the air, "is

abhorrent to everything we stand for."

When asked for a breakdown of how many priests in his diocese abused children

and how many abused teens, Higi refused to say, calling it privileged

information.

Yet Higi clearly is frustrated that critics have "lumped this whole

thing together and said that a tremendous percentage of Catholic clergy

are pedophiles. It simply isn't true."

In the Lafayette Diocese, Sego has been identified as a pedophile. Yet

he did not limit himself to children; he also admits to fondling young

pregnant women. Bohlinger may or may not be a pedophile; he says he can't

remember what his therapists told him about that. The ages of his young

victims mattered little to Bohlinger, who no longer functions as a priest

and says he has not abused anyone since 1986.

At least three other priests were accused by teen-agers or mostly teens;

they are Voss, Wieber and the late Rev. Donald Tracey.

What is a "child?"

Church officials take pains to distinguish a Sego from a Voss.

During interviews with The Indianapolis Star and The Indianapolis

News, Sell repeatedly corrected reporters who used the words "children"

or "minors" when talking about adolescent victims. The vicar

general balked at answering questions until reporters used the word "teenagers."

So sharp is the line drawn that the panel set up by Higi to review sexual

misconduct cases was created expressly to protect children. Accusations

involving teens have not been routinely sent to the Diocesan Review Board,

Sell says.

Sell explains that teens and young adults are of a "different mind-set."

They can "give consent" and understand the kind of "relationship"

they are having.

In fact, he says, some teens are the sexual aggressors.

"The teen-ager might seek to act out in some fashion an expression

of emotion or of attachment or of desire towards the minister," Sell

says. He adds that priests must gently stop those advances, but, "unfortunately,

with the human condition, some of our priests did not."

Sell adds that he's not suggesting that any teen "has led a priest

to stray." It is the priest, he says, who has chosen to commit a

wrong.

Asked when a child becomes a teen, Sell says about age 13. But when asked

again to define a "minor," Sell said the age can depend on the

speed of puberty. For girls, he says, it can happen about age 12: for

boys, about 14.

Yet the diocese's own written protocols for handling sexual misconduct

cases clearly defines a minor as anyone under 18.

If this system for deciding the fates of priest perpetrators seems confusing

or inconsistent, Higi insists it is not. Yet he won't explain, calling

the details of his decisions confidential.

Higi won't even specify what happened to each accused priest. In a scolding

written response to questions from The Star and The News

– questions sent to the bishop after he abruptly cut off interviews

– he wrote that "whether they resigned or were fired or were

granted restricted retirement is basically irrelevant."

He also wouldn't elaborate on Sell's references to teens who "consent."

Higi wrote: "'Consent' as used in the context of your question is

irrelevant."

A matter of trust

Higi is neither a lawyer nor a psychologist, but in this northcentral

Indiana diocese, his word is law. He has no superior in this country;

his boss is Pope John Paul II in Rome.

The bishop wants the public to trust his judgment. He says, with emotion,

that he is doing his "damedest to address this thing."

"How do you capture the pain of this thing?" the bishop asks.

Pain turns to anger for some victims when they hear church officials misstating

their ages, making them appear older than they were at the time of their

abuse.

Sell, for example, puts the ages of Ron Voss' victims at 16, 17 or 18.

But the mother of the young man who died years after being molested by

Voss insists her son was 13 or 14 when the abuse occurred. Other Voss

victims were known to be 15.

Sego has insisted that accuser Linda Schrader was 17 when he had her undress

and dance for him.

"No way, no!" shouts Schrader, who says she was closer to 11

or 12 and "naive as naive can come."

"I didn't even say the word 'sex,'" she says. "Didn't read

it, didn't hear it, didn't see it, didn't know it."

Anyone under 18 is clearly a child in the eyes of David Wilson, a social

worker who runs the diocese's victims' assistance office in Kokomo. Wilson

stresses that his office is not involved in investigating or disciplining

accused priests. To him, it doesn't make any difference whether victims

are 5 or 15.

"They are all children," says Wilson. "They are all hurting

persons. And I am here to help them."

That's the correct response, priests say.

Higi needs to worry about the victims – "who they are, where

they are, what their problems are, if they need any help," said one

priest who asked not to be identified. Are they "angry, bitter? What

healing has taken place?"

Victims and accused priests alike deserve a fair and open process, says

Father Bennett of Crawfordsville.

But Higi, he says, "is in absolute control of this issue and has

been from the very beginning and will be for the foreseeable future. And

this is at his own insistence."

That, Bennett says, is part of the problem.

It clearly is, says Indianapolis attorney Robert Weddle, who has represented

Sego victim Angela Mitchell in a failed lawsuit. Mitchell filed her claim

after the statute of limitations ran out.

Cases go nowhere

Weddle is angry because he believes neither Higi nor the late Bishop Gallagher

reported abuse cases to authorities. By law, suspicions of child abuse

must be disclosed to Child Protective Services or to police.

The attorney says he canvassed seven central Indiana police departments,

none of which had heard from the diocese. One officer, Weddle says, laughed

at him for asking whether the church promptly reports child abuse.

Yet Higi, Sell and Wilson insist they carefully follow the law, promptly

calling child protective officials.

No one knows why, or will say why, such reports never resulted in action.

The cases drop into a bureaucratic black hole where no one is responsible:

Child welfare officials say they can't confirm whether they ever got a

report, police say they did not receive any reports, and prosecutors say

they cannot act until one of the two other agencies does.

"I have been in this office for 16 years and have never heard of

a case against a priest," says Tippecanoe County Prosecutor Jerry

Bean, who prosecutes cases in Lafayette, the city where the bishop lives

and works.

In this diocese, Weddle says, Higi is the law.

"He controls everything. What he says goes."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.