Believers Betrayed

Victims lived in silence for years until the truth began to be uncovered

By Michael D. Sallah and David Yonke

Toledo Blade

December 1, 2002

http://toledoblade.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20021201/SRSHAME/112020034

Second of a three-part series [See also Part 1: Shame, Sin and Secrets and Part 3: Church Struggles to Quell Crisis.]

At the Claar home in Fremont, there was always a seat at the table for Father Bernard Kokocinski. Sunday dinners. Birthday parties. Bike trips along the leafy neighborhood streets that lead to historic St. Joseph parish.

"He was close to everyone," says William Claar, one of three children of Buddy and Louise Claar.

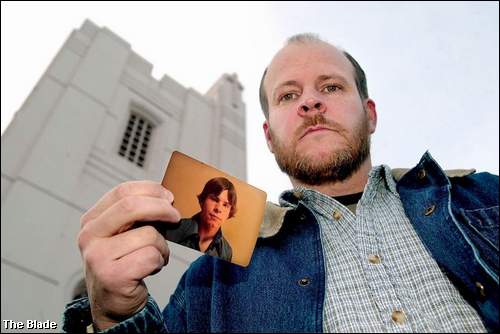

|

William Claar, 43, with a teenage photo of himself, says he was molested repeatedly. Photo by Associated Press. |

But there was another side to the charismatic priest, who earned the trust of the staunch Catholic family in the working-class town.

In the privacy of the rectory in 1975, he repeatedly raped and molested the young boy in sessions that went on for a year, a lawsuit claims.

For most of his life, the youngster lived in shame, transferring to another school and eventually joining the Air Force.

"I never told my parents. I never told anyone," he says. "He was like a member of the family. I didn’t think anyone would believe me."

But last month, encouraged by victims’ stories of clerical abuse, he surprised his family by talking about his anguish and then taking another step: He sued the priest in Lucas County Common Pleas Court on Oct. 18.

Two days later, Mr. Claar’s younger brother, Scott, called with more shocking news: His big brother wasn’t alone.

He too had been repeatedly molested by Father Kokocinski, and he too carried the shame for years, he says.

"He was crying when he called me," says William Claar, now 43. "It all came out - everything."

The brothers soon discovered the man they knew as Father Bernie had a troubled past: arrests on charges of sexual imposition in 1972, soliciting an undercover policeman for sex in 1979, and indecent exposure in 1988, police reports show.

Since his ordination in 1966, he was shuffled to a dozen parishes and took a three-year leave of absence after his last arrest in 1988, diocese records state.

When the brothers came forward, the 64-year-old cleric was forced to step down as pastor of St. Anthony in Columbus Grove on Oct. 22 while the diocese investigates his past. Reached by phone recently, he declined to comment.

The case raises serious questions about whether church leaders protected and concealed a troubled priest - someone who ingratiated himself to a close-knit family, praying with them on holidays and celebrating their birthdays, say the brothers’ lawyers.

A Blade investigation of 24 clergy abuse cases in the Toledo diocese involving children between 1960 and 1994 shows the scenario is not unique.

In 18 cases, the alleged offenders were close to their accusers - students or altar boys - and in 12 of those examples, close to their families.

The Claars are like so many others in the church abuse scandal: They stepped forward because others were doing so.

"It gave me the courage. I guess I realized that I wasn’t alone," says William Claar, who is married and lives in Anchorage.

The trend began in Boston with the controversy of Cardinal Bernard Law’s coverup of pedophile priests, and spread rapidly.

In the Toledo area, 31 people - men and women - were interviewed by The Blade since June. Some cried, and some reacted angrily to memories they say were spawned as long as 45 years ago.

In six cases, victims said they were threatened by priests not to talk, and when they tried, they were met by indifference and sometimes, hostility by church leaders.

Toledo Bishop James Hoffman conceded the diocese did not always respond appropriately to victims in the past, and naively transferred priests who were accused of molesting youngsters to different parishes.

But the 70-year-old spiritual leader said the diocese has gained a deeper insight into clerical abuse, and now embraces zero tolerance.

He said he has met with numerous victims, and has encouraged many to undergo counseling at church expense.

"I always start out by apologizing to the victims for what happened to them," he said in a recent interview. "I just know that if we don’t respond and reach out to victims, that we haven’t done our job."

The bishop, who took office in 1981, said no known incidents of abuse have been reported since the diocese adopted a 1995 policy on sexual abuse.

But even after the policy was enacted, church leaders failed to keep promises to monitor an accused abuser, and in another case, to remove a priest from ministry until The Blade revealed his role on a church tribunal in August.

Twice this year, congregations were misled about their priests’ abuses until the stories were reported by the media.

Church leaders so far have refused to open their secret archives of sexual abuse to the public, but after a two-month delay, they allowed the Lucas County prosecutor to begin reviewing the files on Oct. 15.

Thirteen abuse lawsuits have been filed against the diocese since April, with nine of the cases asking the diocese to open sex misconduct files. Similar legal challenges led to the public disclosure of the Boston archdiocese’s archives in 2001.

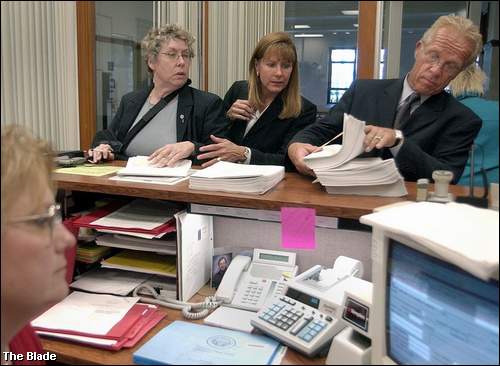

|

Toledo attorney Catherine Hoolahan, left, SNAP President Barbara Blaine, and attorney Jeffrey Anderson file lawsuits. Photo by the Blade / Andy Morrison. |

Trembling hands

On a bright July day, Harold Lee stepped away from reporters near the

Lucas County courthouse, crouched under a shade tree, and lighted a cigarette.

His hands trembling, he couldn’t bear to hear his lawyers talk any more about the former Toledo priest who molested and abused him as a child.

Forty years earlier, he had told his parents and the local prosecutor that the Rev. Leo Welch was sexually abusing him and other boys at a cottage near Lake Erie.

The prosecutor didn’t prosecute. The parish pastor dismissed the story. And the crimes were quietly covered up.

Now, the truth was finally being told at a news conference announcing his lawsuit - two weeks after the former priest admitted "crossing the line" with altar boys in what he called "sexual experimentation."

But for Mr. Lee, 51, the anguish had never subsided.

His case is like so many others emerging since the church crisis exploded this year: He kept silent for decades, too ashamed to talk about his loss of innocence to a man who stood on a holy pedestal.

Unlike many victims, he spoke up right away, but nothing was ever done.

Like half of the 32 victims interviewed by The Blade, Mr. Lee turned to substance abuse as an adult. And in his case, it was alcohol.

Even though he was a plaintiff in a lawsuit, he still struggled with his long-buried emotions at the July 15 news conference.

As the church crisis continues - with more than 300 priests across the country removed from ministry this year - social scientists say they are just starting to understand the complexities of sexual abuse of children by clergy.

For decades, the issue was buried deep in the internal files of the Catholic Church, a subject rarely discussed by society.

Further concealing the problem was the obvious: Victims were reluctant, afraid, or unable to talk about being violated by those whom they believed to be Christ’s representatives on earth.

"We were taught to look up to priests, and to obey them," said Mr. Lee, who lives in Roanoke, Va.

Clerical abuse of children represents 2.8 percent of sex crimes in the country, said Dr. Bernard Cullen, a Medical College of Ohio professor who sits on the diocese’s abuse study committee.

But the psychological damage inflicted by clerics has caused suicides, post-traumatic stress, and severe depression, he says. Many experience a loss of faith and have rejected the church.

For years, Barbara Blaine blamed herself.

"I thought I had sinned. I went to confession. I wanted to get on with my life," says the 47-year-old lawyer.

But she always felt different, she says, and was always "feeling alone."

Her own struggles began in Toledo when, she says, she was sexually abused by a local priest, Chet Warren, starting at age 13.

"He told me that our love was from heaven," she says, "and it was blessed as a gift from God."

She went to Toledo church officials in 1985, who failed to respond to her pleas to remove the priest from ministry, letters and records show.

She said the priest’s religious order, the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales, and the Toledo diocese, told her that she was the first to complain about Father Warren, a popular priest who helped many people.

But when she divulged her story to The Blade in 1992, more women contacted her and church leaders to say they were molested by the priest in what became the area’s first clerical abuse scandal. "I was validated after that," she says.

After hiring a lawyer, Ms. Blaine learned the church had been aware of problems with Father Warren for years.

In fact, 14 years before she reported her abuse, a woman sent a letter to church officials saying she was sexually abused by the priest, said Ms. Blaine.

Another woman, Shelley Killen, said she was sexually abused by Father Warren in 1973, and went immediately to his superiors. She now sits on the diocese’s abuse review panel.

Teresa Bombrys, 41, sued the ex-priest and his religious order in April, saying she was abused from 1970 to 1974 - the first of 13 abuse cases against the local church this year.

In the end, Ms. Blaine received a confidential settlement, and the priest was later stripped of his collar.

But she didn’t stop there: She founded what became the nation’s largest victims’ advocacy group, SNAP - Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests - in Chicago.

A mission to kill

After drinking beer and smoking marijuana in 1989, a former Central Catholic

High School student says he packed a shotgun in his car one night and

sped away. His destination: Crystal Lake in Michigan’s Irish Hills.

His mission: to kill the man that he says raped him - former priest Dennis Gray.

But the former student says after arriving at the cottage 60 miles north of Toledo, "I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. I couldn’t pull the trigger."

Now, 13 years later, the 32-year-old man says he found another way to try to bring closure to his years of struggling with abuse.

He filed a lawsuit Sept. 18 against Mr. Gray and the diocese in Lucas County Common Pleas Court, saying he was assaulted by the priest in what his lawyers are calling a "sexual frenzy."

Eight others have since sued the former Central religion teacher, accusing him of raping them in rectories and at his cottage. All except one, Matt Simon, 33, are using the name John Doe.

Mr. Gray, 54, who recently lost his dean’s job at Toledo public schools after The Blade revealed his troubled past in September, has denied the accusations, saying the accusers are after his money.

But diocesan records say otherwise. In a 1995 letter to an abuse victim, the Rev. Raymond Sheperd, vicar for priests, wrote that the onetime priest "admitted to us that he was guilty of child abuse. He is remorseful, and wishes to apologize.

"He has gone through two different courses of psychotherapy treatment since he left the priesthood."

The man who wanted to kill Mr. Gray says he was once so depressed about what happened to him - from the age of 14 through 17 - that he wanted to commit suicide.

Over and over, the priest took him into his bedroom at the cottage and raped him, saying it was "normal," and that it was for his own good, the lawsuit says.

Sometimes, the alleged abuser would berate the youth, and at one point, struck him on the face.

"His whole thing was putting you down, making you feel so low," says the alleged victim. "He wanted to control you - every part of you."

The victim spent years in counseling, and turned to drugs and alcohol at 17. "I can never begin to tell people how depressed and scared I was."

He said he felt further betrayed because the onetime priest, who gave up his collar in 1987, was a family friend.

"He knew my parents," says the former Central student whose mother went to Father Gray in 1984 and asked him to counsel her son. "He was supposed to make me become a better person because I was getting into trouble."

The 54-year-old woman says her son broke his silence and told her about his anguish in 1995. "It answered so many questions, and at the same time, it broke my heart. I knew all along something had happened to him," she said. "He was restless and angry for so long."

The mother says she feels guilt because she encouraged her son to join Father Gray at his cottage beginning in 1985. She was like many other parents of victims, who were honored that their son was spending time with a priest.

"It was a much more innocent time," said Dr. Joel Kestenbaum, a Rossford psychologist who treats child abuse victims. "Parents would be so pleased that a priest would take an interest" in their child.

When mothers warned their children about strangers, they never envisioned the predators wearing collars.

Parents told their children to "look out for that stereotyped guy: driving a battered vehicle, drooling, wearing grimy clothes," he said, "but not the guy who gave mom and dad communion last Sunday."

|

Connie Davis alleges in a lawsuit against the diocese that she was a resident of St. Anthony Orphanage when she was fondled by the late-Msgr. Michael Doyle. Photo by the Blade / Jeremy Wadsworth. |

The same question

People who were abused by priests are often confronted by the same question:

Why don’t you just get over it?

It happened so long ago.

Psychologists who treat victims say the effects are deeper and more insidious than most traumas and afflictions - and among the least understood.

A child molested by a priest experiences an array of emotions that trigger such coping mechanisms as suppression, denial, and anger - often concealing the real origin of their inner wounds, says Toledo psychologist Chris Layne, who has treated abuse victims.

"I filed it away by slamming it in a cabinet, locking it, and throwing away the key," says William Claar.

Like other male victims, he blamed himself, questioning his own sexuality, and keeping his secret from those closest to him. "I had all these thoughts: Was I gay? Was I normal?"

Compounding their inner struggles was that their perpetrators were part of a powerful - and revered - institution that concealed the problem for decades, says church sociologist A.W. Richard Sipe, of La Jolla, Calif.

Many victims grew up not even knowing the source of their pain. For Connie Davis, it was during a counseling session in 1997 when she finally broke down.

After two failed marriages, bouts with alcohol and drugs, and years of denial, the images of Msgr. Michael Doyle wouldn’t disappear, she says.

"All of a sudden, I was shaking. I started crying," says the 56-year-old woman.

She says her abuse at St. Anthony Orphanage began when she was 8 years old in 1954, when the now-deceased priest called her into his office, ordered her to sit on his lap, and slipped his hand under her panties, her lawsuit alleges.

It was the first of many sessions that took place until she was removed from the facility at age 12 for telling the nuns about the secret sessions, her lawsuit alleges.

But this wasn’t just any priest. This was Monsignor Doyle, a noted Toledo political figure, labor mediator, and social service advocate whose name appears on a wing of the diocese’s headquarters.

"I was slapped when I told them," she says.

Four decades later, one of her demands to the diocese is to remove the late cleric’s name and portrait from the church’s headquarters.

The case is particularly thorny for two reasons: the cleric died in 1987 at the age of 88, and the accuser’s half-sister has since told the diocese she was unaware of her sibling’s alleged abuse.

But since Ms. Davis’ lawsuit on Oct. 18, two other women have emerged to say they too were molested by the prominent cleric at the orphanage between 1954 and 1959 - with one of the accusers under treatment by a psychologist, say SNAP coordinators and lawyer David Zoll.

"Connie Davis was never alone," says Mr. Zoll.

Since the church crisis began this year, the local victims who have stepped forward vary in age, background, and stage of healing, but they’re united in their sense of betrayal. For some, the anger endures.

"It’s not about priest-bashing, because most priests are good people, and we shouldn’t lose sight of that," says William Claar.

"This is about pedophile priest-bashing. This is about exposing priests who should have been exposed a long time ago."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.