DANNY'S STORY | DEATH OF AN ALTAR BOY

A priest, a boy, a mystery

By Kevin Cullen

Boston Globe

December 14, 2003

The nightmares are frequent and always end the same way: Bunny Croteau wakes up in a cold sweat, swinging clenched fists, crying for her son.

"Danny is yelling for help," she says, staring out the window of her living room, "and I can't get to him."

|

| Carl and Bunny Croteau believe a priest was behind the slaying of their son 31 years ago. Globe Staff Photo/Dominic Chavez |

Danny Croteau was 13 when they found his body, floating face down in the Chicopee River, a few miles from his Springfield home. That was 31 years ago. But for Bernice "Bunny" Croteau and her husband, Carl, the anger and frustration only grow as the years pass.

Living with the nagging sense that they didn't do enough to protect their youngest son is bad enough. Knowing that the man they believe killed him is still out there, living in retirement only a few miles away, haunts them. Knowing that that man remains a priest, paid by their diocese, drives them crazy."The world's upside down, and there is no justice," Bunny says, looking over to her husband, who nods.

It is not only the Croteaus who believe that the Rev. Richard R. Lavigne, a convicted child molester, murdered their son in 1972, crushing his skull with a rock and dumping his body in the river. Just about every law enforcement official who worked on the case believes Lavigne did it.

To this day, the case remains open, and the priest is, as he has been for three decades, the only suspect, according to law enforcement sources.

"What really bothers me and Bunny is that whatever police we talk to, they say, `We know who it is,' but they can't charge him," Carl says. While police and prosecutors long ago assembled a circumstantial case against Lavigne, the lack of physical evidence and of witnesses placing him with Danny the night of the murder have made authorities reluctant to charge him. DNA testing of blood found at the scene was inconclusive. Lavigne's lawyer, Max Stern, is adamant that his client is innocent.

"He didn't do it," Stern says.

But while the question of who killed Danny Croteau is unanswered -- and may never be answered -- more certain is that the Diocese of Springfield knew Lavigne was a suspect, and knew of sexual abuse complaints against him, and yet allowed him access as a priest to children for 20 years after the murder.

|

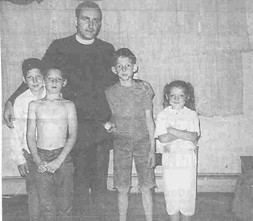

| NOT TALKING "My silence has been my salvation," is all the Rev. Richard Lavigne will say today about the case. Below, Lavigne poses with (from left) Joseph, Danny, Michael, and Jackie Croteau. Globe Staff Photos/Dominic Chavez |

|

During that time, according to police who have investigated him and the nearly 40 people who have filed lawsuits against him, Lavigne abused scores of children. In 1992 he was convicted of fondling two boys and sentenced to probation. In 1994 the diocese paid $1.4 million to settle claims brought by 17 people who said Lavigne abused them, and Lavigne now faces another 20 claims. The Massachusetts Sex Offenders Registry Board classified Lavigne as a Level 3 offender, meaning he is deemed a high risk to reoffend.

He remains, for many in heavily Catholic western Massachusetts, the living symbol of the clergy abuse crisis, much as John Geoghan was in Boston.

One difference: Lavigne is still a priest, though the Springfield Diocese removed him from active service in 1991 and earlier this year began the process of defrocking him. Another: Lavigne has never gone to jail.

More than a lack of physical evidence has kept Lavigne a free man. He has been the beneficiary of cultural attitudes that made many, including the Croteaus at first, refuse to believe a priest was capable of such abhorrent acts.

Law enforcement, especially in the early going, was likewise deferential. Prosecutors shrank from seeking warrants to search his family home and the parish rectory. Even after Lavigne pleaded guilty to the two abuse counts, the judge in the case declined to send him to jail, saying the charges were overblown.

Today, the murder case is still under active investigation, Hampden County District Attorney William M. Bennett says. A new series of DNA tests has been ordered.

And there is a corps of police officers who refuse to give up on trying to put Lavigne in jail, if not for Danny Croteau's murder, then for sexual abuse. Lavigne is a suspect in an ongoing investigation into the sexual assault of a boy in the 1990s, according to people familiar with that investigation.

As police and prosecutors slowly proceed, Bunny and Carl Croteau are left to reflect on the tragedy that upended their family life forever but, remarkably, did not steal their faith.

Just 7 miles away from the Croteau home, Richard Lavigne lives on a quiet street in Chicopee, with his elderly mother, supported by a $1,030 monthly check from the diocese.

One recent afternoon, Lavigne was putting a fresh coat of white paint on the house. At 62, he is fit and trim, though friends say he has a heart condition. He told a Globe reporter he wanted to tell his side of the story but had been advised over the years not to.

"My silence," he said, "has been my salvation."

`He said he wanted to help us'

Carl and Bunny Croteau have been married for 51 years. They have lived

in the same brick ranch house in the Sixteen Acres section of Springfield

for 38 years. They raised seven children, five boys, then two girls. Danny

was the youngest boy.

A painting of Danny, inspired by his seventh-grade school photograph, has hung in the same spot in the living room for 31 years. Wedged behind the framed portrait is a pair of withered palms from Palm Sunday last April. On the other side of the living room is a lamp Bunny made in the shape of Huckleberry Finn -- the mischievous, adventurous character reminds her so much of her lost son.

|

| COMFORTING THE VICTIMS The Rev. James Scahill, who has become a confidante of some who say they were victimized by Lavigne, walks through Springfield's St. Michael's Cemetery with one such person, Peter Bessone, who says he wants to see Lavigne defrocked. |

His parents remember Danny as a bright, loquacious boy with freckles and strawberry blonde hair who loved to go fishing. He had a generous side. He used to help an elderly woman in the neighborhood, fetching her mail, raking her lawn, doing errands.

"She'd give him milk and cookies," his mother says. "That's all he wanted."

Sometimes, when she longs to hear his voice, Bunny pulls out a small RCA boombox and pops in a cassette. It is a tape the family made, a few months before Danny was murdered. At one point Danny can be heard talking about a religious medal his mother had given him. Danny had already decided whom he would give the medal to.

"Father Lavigne will love the medal," Danny said.

Five years earlier, after he was assigned to their parish, St. Catherine of Siena, Lavigne arrived on the Croteau doorstep.

"He just popped up here all of a sudden," Bunny says. "We didn't invite him. . . . He said he wanted to help us."

Carl, who was often working two or three jobs at a time, says they were grateful for the help.

"He knew we had a big family," Carl says. "Things were tough. I'd get laid off sometimes. Lavigne would raid the freezer at the rectory and bring us steak or a roast. He offered to look after the kids, to baby-sit them."

All five of the Croteau boys served as altar boys at St. Catherine's. Police say Lavigne worked to gain their trust. Sleepovers at the rectory became common for some of the boys. Lavigne also had some stay with him at his parents' Chicopee home. One day, 14-year-old Joe Croteau came home hung over after a sleepover. Lavigne told Carl that Joe had gotten into his parents' liquor cabinet without his knowing.

"Like a fool, I chastised Joe," Carl says.

Lavigne was, from the start, a charismatic and controversial figure at St. Catherine's and, later, at St. Mary's, another local parish. He would roar at anyone who walked in late for Mass. He spoke out against the Vietnam War. In an area where military service was a proud tradition, his views made some parishoners uncomfortable.

But he flattered others with attention. It was a time and a place where having a priest come to dinner or take the children for sleepovers was a status symbol.

On Friday, April 14, 1972, the last day Danny was seen alive, he came home from school and helped his mother put a rug down. Sometime between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m., she said, he went out to play. She never saw him again.

When Danny didn't come home that night, his parents began calling around. Bunny called Lavigne, but he said he hadn't seen Danny. As the hours passed, Bunny and Carl began to panic. At 2:11 a.m., they reported Danny missing to the police. At 8:25 a.m., a fisherman saw Danny's body floating in the Chicopee River, under the Robinson Bridge, near the Springfield line. Inside the pocket of the boy's suede jacket police found his blue school tie and a yellow exam paper.

|

| KEEPING THE FAITH Despite all he has gone through, Carl Croteau assists during Mass at St. Catherine's, just as his youngest son, Danny, did more than 30 years ago. |

Carl rushed home from work when he got the call. The police there told

him he should go to the Chicopee police station. On the way, he stopped

at the rectory to tell Lavigne.

"They found Danny murdered," Carl blurted out, trying to control his emotions.

Lavigne betrayed none of his own, according to Carl. "Do you want me to come along?" the priest asked. Carl was glad for the company.

The Chicopee police station was buzzing. Carl met the detectives who would hunt his son's killer. After police told Carl that Danny had been taken to a nearby funeral home, Lavigne offered to identify the body. Carl thanked Lavigne, relieved he didn't have to face that horror himself.

Suspicions raised

The day after Danny's body was found, Chicopee Police Lieutenant Edmund

Radwanski was out studying the crime scene when he noticed Lavigne, walking

along the riverbank. He arranged to interview the priest the next day.

In his official report on their conversation, Radwanski noted that Lavigne asked him two questions that he and other investigators considered strange -- and possibly incriminating.

"If a stone was used and thrown in the river, would the blood still be on it?" Lavigne asked, according to the report.

How could the priest have known to ask, investigators wondered. There had been, to that point, no public disclosure about how Danny had been killed. It would be several weeks, in fact, before police told the Croteaus that, based on the wounds, they believed Danny had been killed by a left-handed assailant wielding a stone. Lavigne is left-handed.

Lavigne also stirred Radwanski's suspicions when he asked about the tire-track prints taken by police at the scene.

"In such a popular hangout with so many cars and footprints," the priest wondered, "how can the prints you have be of any help?"

The priest, in his session with Radwanski, also gave the first of several inconsistent statements about his relationship with Danny.

Lavigne told Radwanski that whenever he took Danny anywhere, it had always been "with his brothers or a gang of kids." Within days of the murder, however, police learned from the Croteaus that Lavigne, in fact, had regularly been alone with Danny.

A Chicopee woman who lived near Lavigne's parents' home told police that on April 7, a week before he disappeared, Danny had appeared at her door at 10:30 p.m., saying he was lost and asking to use her phone to call Father Lavigne. Five minutes later, a maroon Ford Mustang like the one driven by Lavigne pulled up and picked Danny up. When questioned about the woman's account, Lavigne admitted to Radwanski that he had picked up Danny and taken him, alone, to his parents' house in the Aldenville section of Chicopee, where Danny spent the night.

Bunny Croteau told police that Danny had arrived home on the morning of April 8, said he felt ill, and later threw up repeatedly. Police believe Danny had been given alcohol by Lavigne the night before, but when questioned after the murder, Lavigne denied it. The priest did, however, acknowledge that Danny might have gotten into his parents' liquor cabinet.

Autopsy tests showed that Danny was drunk when he was killed. His father said police told him his son's blood alcohol content was nearly double the level that would have rendered him legally intoxicated. Police say Lavigne's pattern was to ply boys with alcohol before abusing them.

Bunny's sister Betty flew in from California for the funeral. Lavigne greeted her at the Croteau home. He told her that he had identified the body, and that it was important to convince Carl and Bunny to keep the casket closed for the wake. Danny's face was mangled, Lavigne told Betty, and his mother shouldn't see him that way. Betty did as instructed by the priest.

After the funeral, State Police Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon, the lead investigator on the case, came by the house to offer his sympathies and pose some questions. He asked the Croteaus why they kept the casket closed. When they explained, the veteran officer shook his head. Danny's face wasn't disfigured at all. The wounds were to the back of his head.

The family was baffled by Lavigne's behavior at the time, but now they have a theory.

"I think Lavigne couldn't bear to look at Danny's face again," Carl Croteau says.

Fitzgibbon then talked to each of Danny's brothers separately in one of the bedrooms, while Carl and Bunny waited in the living room. Then he told the couple what he had learned: Their sons said Lavigne had sexually abused some of them. At first, Carl and Bunny couldn't believe it. To this day, they say, they haven't had a heart-to-heart with any of their sons about Lavigne. It is a subject the family just can't talk about.

"Our boys blame themselves for Danny's death," Carl says. "It haunts them. It haunts us."

In 1996 Joseph Croteau settled a lawsuit against the diocese for the sexual abuse he says he suffered at the hands of Richard Lavigne.

The investigation

If Danny's rakish ways reminded his parents of Huck Finn, Jim Mitchell,

a now retired state trooper who helped investigate the murder, remembers

thinking of the 13-year-old as a boy trying to grow up too fast.

"He would hitchhike around regularly," Mitchell says.

And he made some questionable friends.

"There was a produce manager at a nearby supermarket," Mitchell says, "and Danny went to his house and painted his bedroom."

Mitchell says both the produce manager and another man who led the Boy Scout troop to which Danny belonged were questioned after the murder. But Mitchell says neither "rose to the level" of suspicion that Lavigne did, and that after their alibis checked out, they were ruled out as suspects.

As police worked the case, they asked the Croteaus to alert them if they noticed anyone acting strangely at Danny's wake.

There was one such person: a Franciscan priest, in brown robe and sandals, who wept loudly as he stood in front of the casket.

"It was just so odd, because we didn't know this priest, and no one else seemed to know him," Bunny says.

Mitchell looked at the condolence book and found the name Father Barnabas, whom he traced to the St. Francis of Assisi Center in downtown Springfield. When Mitchell met Father Barnabas Keck at his chapel office, he noticed that the only thing tacked to a cork bulletin board behind the priest was a newspaper story about Danny's murder.

"Why did you go to the wake, Father?" Mitchell remembers asking. "Do you know the family?"

No, the priest replied.

"Do you always go to the wakes of people you don't know?" Mitchell asked.

No, the priest replied. But the murder of the boy moved him so deeply he felt he should pay his respects.

Mitchell returned to his office and pulled aside his boss, Fitzgibbon.

"Fitzy," he said, "there's something very peculiar over there."

A few weeks later a high school student contacted State Police, saying he wanted to give a statement about what happened to him when he stayed overnight at St. Mary's rectory with Father Lavigne. The boy told Mitchell that Lavigne gave him alcohol and fondled him. After one of the sleepovers, the boy said, Lavigne took him to the St. Francis Center, saying they needed to go to confession.

Mitchell and Fitzgibbon believed that Father Barnabas was Lavigne's confessor. But because Massachusetts law protects priest-penitent confidentiality, they couldn't make him talk about it.

Reached in New Paltz, N.Y., where he is serving as a priest, the 79-year-old Keck said no one has ever confessed to him about the murder of Danny Croteau. Keck said that many Springfield priests used the St. Francis chapel for confession, but that he never saw the faces of the penitents.

"I knew of Father Lavigne, but I never met him face to face," Keck said. "I wouldn't have recognized him."

In the immediate aftermath of Danny's murder, Carl and Bunny could not comprehend what had happened to Danny, and couldn't countenance the idea that Lavigne had played a role.

But Lavigne was soon aware of what police suspected. Within days of presiding over Danny's funeral, Lavigne called Bunny.

"Under the circumstances," he told her, "I think it's best that I don't come around for now."

They never spoke again.

Later, as her suspicions grew, Bunny tore around the house like a tornado, looking for photos of her sons with Lavigne, ripping them up.

"I didn't want any reminders of him," she says.

Lavigne told the Globe he had considered communicating with the family but never did. He doesn't think he could talk to Carl Croteau.

"He's so bitter," Lavigne said.

Priest seemed `untouchable'

Carl Croteau says Fitzgibbon, who died in 1982, told him "a lot of

mistakes were made" in the early days of the murder probe. One was

the failure of police and the district attorney's office to push harder

to search St. Mary's rectory, and to examine the clothes the priest wore

the night of Danny's death.

"The police went there, but the priest who answered the door wouldn't let them in," Carl says Fitzgibbon told him.

Mitchell says police didn't have enough evidence to get a warrant. But other officers suggest Lavigne's conflicting statements about Danny and his odd remarks at the crime scene might have met the probable cause threshold -- but not for a search of a church rectory, in Springfield, in 1972.

Bishop Christopher J. Weldon, then head of the Springfield diocese, and Matthew J. Ryan Jr., then district attorney, were well known to be good friends. The Croteaus and others believe that friendship made Ryan less aggressive in pursuing the case.

In an interview, Ryan, now retired, denied he went easy on Lavigne. Ryan said that he, too, believes Lavigne was the killer, but that he did not have the evidence to seek an indictment for the murder or for Lavigne's sexual abuses.

"What you think and what you can prove in court are two different things," Ryan said.

Carl Croteau says he clashed with Ryan, asking why the district attorney wouldn't at least go after Lavigne for molestation. He says Ryan told him it would have endangered the murder investigation to do so.

Ryan told the Globe he didn't prosecute Lavigne for abuse because none of the victims would come forward.

There is evidence that some victims of Lavigne remained silent out of fear of Lavigne. In a series of interviews, several men said they were, as boys, abused by Lavigne but kept quiet because the priest seemed untouchable.

"Everyone around here knew that the police thought Lavigne killed Danny Croteau," said Stephen Block, who says Lavigne began sexually abusing him shortly after the murder. "After I saw that nothing happened to Lavigne, there was no way I was going to come forward."

Block has since sued the diocese.

Ryan's reluctance to prosecute Lavigne for sexual abuse hit close to home. Ten years ago, two of his nephews came forward to say Lavigne had molested them.

The diocese's role

The Springfield Diocese says the first complaint it received about Lavigne came in 1986. But Mitchell, the retired State Police officer, said that shortly after the murder, Fitzgibbon briefed diocesan officials on what police had learned about Lavigne's molesting some of the Croteau boys and others.

"We had an obligation to show our cards," Mitchell says. "Fitzy had a sit-down with them. Everything we knew, we told them."

As the diocese contests nearly two dozen pending claims against Lavigne, what its officials knew and when they knew it remains a point of enormous contention. But the diocese's own records suggest it had been informed by police that Lavigne was a suspect in the murder case. Within three weeks of the murder, on May 4, 1972, diocesan lawyers arranged for Lavigne to take a polygraph. According to an account of the examination, which is included in the portion of Lavigne's personnel records that has been turned over to John J. Stobierski, a Greenfield attorney representing alleged Lavigne victims, he was asked five questions:

Did you strike Danny Croteau's head to cause his death?

Did you kill Danny Croteau?

Were you present when Danny Croteau was killed?

Did you dump Danny Croteau's body in the Chicopee River?

Do you know who killed Danny Croteau?

Lavigne answered no to all five questions, but the examiner said, "Due to these erratic and inconsistent responses on this subject's polygraph records, the examiner is unable to render a definite opinion as to the subject's truthfulness."

The diocese then arranged for Lavigne to travel to Chicago, where on May 9, 1972, he passed a pair of polygraph exams asking the same questions, the released records show. From that point on, diocesan lawyers pointed to the polygraph tests as proof that Lavigne did not kill Danny Croteau. The diocese allowed Lavigne to remain in parish work, with no restrictions.

After Lavigne was charged in 1991 with sexually assaulting five boys, Bennett, who had succeeded Ryan, reopened the murder probe. With Lavigne's image of invincibility shattered, more people came forward.

One of the new witnesses was Carl Croteau Jr., who recalled that on the day before his brother's funeral, he answered the telephone at his family's home. A male voice said: "We're very sorry what happened to Danny. He saw something behind `The Circle' he shouldn't have seen. It was an accident."

Whoever called would not identify himself, but Carl Croteau Jr. told

police he is certain the caller was Lavigne. Investigators believe Lavigne

was trying to throw them off his scent. "The Circle" referred

to by the caller was a notorious teen hangout behind the Sixteen Acres

library.

An odd encounter

And just last year, Sandra Tessier, one of Lavigne's former parishioners

at St. Mary's, gave police a statement about an odd encounter with Lavigne.

Within weeks of the murder, Tessier was awakened at 3:30 a.m. by a phone call. It was Lavigne. He asked to meet her at a nearby all-night diner. Still half asleep, Tessier got dressed and drove over. She says the conversation went like this:

"I want to prove to you that I didn't murder Danny Croteau," Lavigne told her as soon as she arrived.

"Father, why would I think that?" Tessier replied.

Lavigne steered her toward a man who, while in plain clothes, flashed a badge and said he was a police officer. The man told Tessier that Lavigne had nothing to do with the murder.

"See," Lavigne said, turning to Tessier. "I told you I didn't do it.'

"I kept saying, `I never thought you did do it.' But as time went on, I kept thinking, `Doth protest too much,' " Tessier recalled in an interview.

While police have not been able to place Lavigne at the murder scene the night Danny was killed, they have evidence that Lavigne was familiar with the spot. Joe Croteau told police that sometime in 1971, Lavigne took him fishing there.

The crime scene proved a challenge to investigators trying to find physical evidence that could help them find the killer. The place where Danny's body was found was a fishing hole by day and something of a lovers' lane at night.

Police combed the site and submitted some objects for forensic testing, which revealed two types of blood: Type O, which was Danny's type, and Type B, which is the type of about 9 percent of the population, including Richard Lavigne. But DNA testing, which can link blood samples to particular individuals, had not been developed back then. After the case was reopened in 1991, a piece of rope and a plastic straw with traces of Type B blood on them were submitted for DNA testing. The forensic scientist who conducted the tests said that the blood on the straw was not Lavigne's, but that he could not rule out that the blood on the rope might be. Lavigne's lawyers say the testing is proof Lavigne is innocent. Prosecutors call it inconclusive. Bennett said his office has commissioned a new round of DNA testing.Unless the new results conclusively link the blood to Lavigne, it is unlikely he will ever face murder charges, according to police who have worked on the case. Bennett, in an interview, says that to seek an indictment prosecutors must believe a suspect is guilty, and have sufficient credible evidence to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. While Bennett would not say so, other law enforcement sources say prosecutors don't feel their case clears the "reasonable doubt" hurdle.

Carl Croteau says Bennett has told him he could probably get an indictment, but not a conviction. But Croteau believes the evidence would sway a jury.

"If he was acquitted, we could live with that," he says. "But why not take a shot? I think we owe that much to Danny."

And to the others who trace the fracturing of their lives to Lavigne. Peter Bessone and his cousin, David Bessone, were among them. They were like brothers. They played together. They went to school together. And one day they vowed to keep a secret together: Both said their parish priest, Father Lavigne, was molesting them. Peter was 8. David was 9.

As the boys grew up, Peter sank into a haze of drug and alcohol abuse. David left the state and went to college.

At Christmas time in 1985, David called Peter to beg him to get off drugs. Then David hung up the phone, lit a Hibachi grill in his apartment, lay down, and let the fumes fill his lungs. He was 23.

A few weeks ago, Peter Bessone watched as a priest, the Rev. James J. Scahill, knelt at David's grave at St. Michael's Cemetery in Springfield, to say a prayer.

"The ground was soaking wet, but Father Scahill knelt down anyway," Peter said.

Peter knelt, too, and then collapsed into the priest's arms and wept.

Scahill has become a confidante and spiritual counselor to Bessone and others allegedly abused by Lavigne. Scahill has also become the accusing finger pointed at his own bishop and diocese. For more than a year, Scahill has refused to give the diocese its traditional 6 percent cut of the weekly collection from the parish -- Springfield's most affluent -- to protest Bishop Thomas L. Dupre's continued financial support of Lavigne.

Scahill says the diocese has been aware of Lavigne's predatory ways since at least 1972, when Lavigne became the prime suspect in Danny Croteau's murder.

"I think Lavigne has gotten away with murder for more than 30 years," said Scahill, sitting in the living room of St. Michael's rectory in East Longmeadow. "But the people who have enabled him are worse than him."

In 1988, Scahill was posted to St. Mary's, where Lavigne served in the 1970s. After Lavigne's arrest in 1991, some people came forward to say Lavigne had molested them, too. Over the years, Scahill counseled a half-dozen of Lavigne's victims.

Some became outright suicides, like David Bessone. But there are others whose downward spiral was gradual.

"They kill themselves by inches," Scahill says, as he steers his creaky 1988 Buick through the streets of Springfield, glancing at Peter Bessone, who sits glumly in the passenger seat.

Scahill got to know Peter 11 years ago, when Bessone's father was dying of cancer. Scahill visited the father in the hospital, but the son wanted no part of a priest. At each visit, Scahill put out his hand. Peter would just scowl.

"For a month, I ignored his hand," Peter says. "At my dad's funeral, Father Scahill came up to me and said, `I'm here if you need me.' I don't know why, but I shook his hand. I remember whenever Father Lavigne was molesting me, his hands were cold. Father Scahill's hand was warm."

Bessone, 40, is in the advanced stages of leukemia. He says he does not know how long he has to live, but he hopes to live long enough to see Lavigne defrocked.

Dupre declined to be interviewed. But on the diocese's website, he defends the support of Lavigne: "Our obligations continue even to those who have grievously sinned and caused enormous harm. Those teachings of forgiveness and charity are core values of a Catholic Christian belief, and I cannot deviate from them even though it would be the popular thing to do."

`It's ruined the family'

Despite all they have gone through, Carl and Bunny Croteau cling fiercely

to their Catholic faith. Each day, Carl goes to St. Catherine's to attend

Mass. Some days, he acts as an altar server, assisting the priest as Danny

once did. Other days, he serves as a eucharistic minister, handing out

Communion, as Lavigne once did. Carl Croteau believes firmly that if Lavigne

escapes justice in this world, he will face it in another.

Hillcrest Park Cemetery is just a mile from the Croteau home. It is a peaceful place, with towering trees and a picturesque pond. Carl goes often, to visit his youngest son's grave.

He points to the empty plot to the left of Danny's grave.

"Bun and I will be next to him," he says, then bends down to touch the ground.

"It's ruined the family," he says, almost in a whisper. "We have kids we can't talk to about it. It never leaves you. You never have that peace."

Back at the house, Bunny Croteau sits in the corner of her living room, knitting. She has little and wants less. She has her faith, her nine grandchildren, five great-grandchildren, a few photos, a tape of Danny's voice, and the nightmares.

"The last time I had the nightmare with Lavigne in it," she

says, softly, the afternoon light fading so that Danny's portrait on the

opposite wall is bathed in shadow, "I was swinging at him, hitting

him with everything I had. But then I woke up, and there was nothing there.

I was crying. I was calling out for Danny. And there was nothing there.

Nothing."

| BishopAccountability.org Home | Springfield MA | Resources | Timeline | Assignment Record Project | Settlements | Treatment Centers | Transfers | Bishops and Dioceses | Legal Documents Project | Diocesan Web Sites Project |

FAIR USE NOTICE: In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this Web site posts certain copyrighted material without profit for members of the public who are interested in this material for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this Web site for purposes of your own that go beyond “fair use,” you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. If you have questions regarding some of the material posted on this Web site you may contact us at staff@bishop-accountability.org.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.